A RECONSTRUCTED HUERTA FOR

MISSION SAN FERNANDO REY DE ESPANA

SAN FERNANDO, CALIFORNIA, FOUNDED 1797

By James J. Sagmiller

HISTORY

During the period of Spanish exploration of North America (1542-1769) and the Spanish Colonial period (1769-1821) the area we presently call California was known as “Alta California,” which translates to “Upper California.” Baja California, or “Lower California” retains its original name today. The policy of the Spanish crown was to establish Catholic missions to convert native peoples and exploit them for labor. Priests were sent out in pairs, usually with regional support of the military. The first successful, permanent mission in the area was founded in Baja California: Mission Nuestra Senora de Loreto Concho, on Oct. 9, 1697 by Jesuit priests. The king of Spain expelled all the Jesuits in 1768, responding to rumors they had become too powerful. The Jesuits were replaced by Franciscan friars who, as part of the philosophy of their order, are required to take a vow of poverty. Around this time, the Spanish crown decided to establish missions and develop ports in Alta California. Mission San Diego Alcala was the first of these, founded July 16, 1769.

FOUNDING THE MISSION

Several criteria were important for a successful mission: fertile soil, water available for irrigation and drinking, standing timber for building, and a native population that could be converted to Christianity and used for labor.

Mission San Fernando Rey de Espana was founded September 8, 1797 by Padre Fermin Fransisco de Lasuen. It was the seventeenth of the missions founded in Alta California. A man named Francisco Reyes already had a ranch at the site of the mission and it was worked with Native American labor. He decided to donated his land to the church. At an elevation of 1,100 ft., with reliable spring water, a mild coastal climate and twelve inches of rain a year, this was an excellent place to start a mission. The native population originally were hunter gatherers who exploited the rich flora and fauna of the area. Several tribal groups lived nearby, but the two most numerous were the Gabrielino and Tataviam Indians.

THE SITE

The site plan of Mission San Fernando Rey de Espana was of a design typical for Spanish missions. The main focus of the mission complex was the chapel, with its rectangular central nave with altar, and a bell tower adjacent. Other buildings, mostly workshops, were arranged in the pattern of a quadrangle around a large patio (now known as the East Garden). A soldier’s quarters were located behind, next to the chapel, and a cemetery to the north. A building designed as priest’s quarters and for guest lodgers was the well-known and much-photographed structure with an arched arcade known as the “convento.” The arrangement of buildings in the compound was designed for efficiency but also for protection from bandits, wild animals, and livestock. Irrigated gardens benefited from this protection and were convenient to the kitchen.

The buildings at the mission were built of adobe bricks, made from a mixture of mud and straw and had very thick walls made to support heavy beams and tile roofs. Pine logs were used for beams and the rafters made from sycamore. Eaves were very wide, to protect the adobe from rain.

ECONOMICS OF THE MISSION

The mission was, of necessity, primarily self-sufficient. Natives were trained in many trades, including: blacksmithing, farming, ranching, carpentry, weaving, leather-making, brick-making, and soap-making. Wine was made from grapes and olive oil as well. By 1804, 1,000 Native Americans lived and worked at Mission San Fernando Rey, producing hides, fine leatherwork, tallow, soap, cloth, and wine as well as all the crops needed to support so many. By 1819 there were 12,800 cattle, 7,800 sheep, 176 goats, 45 pigs, 144 mules, 780 horses. The mission was a popular resting place for travelers on El Camino Real (the Royal Road).

HISTORIC MISSION GARDEN

Every mission had to produce as much food as possible to feed its large labor force and create a reserve to act as insurance for famine. Each of the missions planned extensive gardens. These gardens were not the primarily ornamental ones we see today at the missions, but were subsistence gardens of vegetables, fruit, herbs and flowers, all grown together. A garden of this type was referred to as a “huerta.” A literal translation would be “orchard garden.” These gardens looked quite different than modern gardens. They had geometric beds set into dirt or gravel paths, filled with plants grown together in a practical fashion, watered by flood irrigation from “acequias,” small irrigation ditches of gravity-fed water. There was no lawn grass. Everything grown was used for some purpose, such as for food, medicine, dye, cosmetics, wine, or oil.

MISSION GARDENS TODAY

An early photograph shows the East Garden in a ruined state before the workshop buildings were reconstructed. A fountain was originally in the center of the garden, but it was moved about 30 feet to the west and the original design of the garden obliterated as the workshop buildings were rebuilt. What we see now in the East Garden are cement paths set into grass, with various hedges and shrubs, and olive, pine and palm trees. I am presenting here a design for the reconstruction of the huerta that originally occupied the space that is now the East garden, as it might have appeared circa 1804.

A RECONSTRUCTION OF THE EAST GARDEN

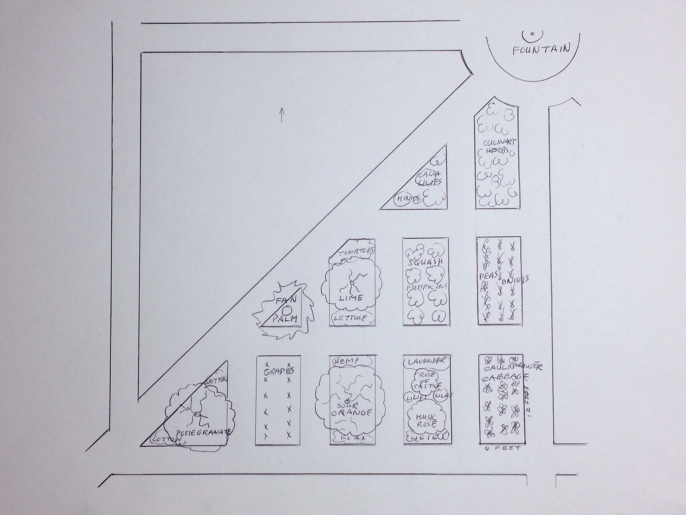

In my design for a reconstructed huerta at the mission, the fountain would be returned to the center of the design, with paths leading in four directions from the fountain as well as a path to each of the four corners of the quadrangle. All lawn grass would be removed, and original gravity-fed irrigation ditches, called “acequias,” would be reconstructed as well. The mature olive, palm and pine trees would be left in place, as the use of those species were very much a part of original plantings at the 1797 mission. Paths would be made of ¼ inch gravel and geometric beds would be flood irrigated just as they originally were. Every effort would be made to source seeds and cuttings of original plants known to have been grown at the California missions in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Plants requiring irrigation were the most likely candidates to be grown in the huerta, such as fruits, flowers and vegetables.

HISTORIC PLANTS GROWN AT THE MISSIONS

Wheat, corn (maize) and barley were grown at Mission San Fernando Rey, but most probably in outer fields or dryland farmed. Vegetables that were probably grown in the irrigated huerta and appearing on mission records include: peas, beans, fava beans, cabbage, lettuce, asparagus, onions, tomatoes and chili peppers. Several fruits were grown at the mission: oranges, melons, pears, grapes, pomegranates, apples, quinces, plums, peaches, apricots, figs, olives, avocados and watermelons. Wild plants were also used at the mission. Presumably the Native Americans introduced the padres to them, for they are an excellent, readily available food source. Wild plants and seeds known to have been used at the mission are: chia (Salvia hispanica), sunflowers, acorns, pine nuts, sage, tunas (the fruit of Opuntia spp. cacti), clover, screw beans (mesquite; Prosopis spp.), “nopales” (leaves of Opuntia spp. Cacti) and agave. The chia was probably brought from Mexico.

In a reconstruction of a huerta for Mission San Fernando Rey it was advantageous to consult historic documents from other, contemporary California missions. Records from Mission San Diego dated 1769, reveal that corn (maize), cauliflower, lentils and garlic were grown there. By the 1770s grapes, barley, wheat, lettuce, figs, peppers, squash and pumpkins were grown. By the 1790s, records show that apples, pomegranates, oranges were grown as well. Herbs grown at Mission Santa Barbara included: anise, basil, borage, cilantro, cumin, dill, epazote (Dysphania ambrosioides), horehound, lavender, mint, rosemary, sage, thyme, and valerian. Father Junipero Serra brought the castor oil plant to Mission San Diego in 1769 and the plant was used for its oil. Other early introductions grown at many of the missions (Padilla 1962; Streatfield, 1994) were: calla lilies, Madonna lilies (Lilium candidum), the Castilian rose (Rosa x damascena bifera), the musk rose (Rosa moschata), jasmine, pennyroyal, wild cherry (Prunus illicifolia), Peruvian pepper tree (Schinus molle), matilija poppy (Romneya coulteri), date palm Phoenix dactylifera), Canary Island date palm (Phoenix canariensis), Mexican fan palm (Washingtonia robusta) and native fan palm (Washingtonia filifera).

Utilitarian plants known to have been grown at most of the missions include: agave, cotton, flax and hemp—all used for fiber. Teasel was used for making combs to card wool. Indigo was grown for dye and palm fronds were used for roof thatching and for making brooms. The giant reed (Arundo donax) was used in ramadas to provide slatted shade. Gourds were raised to be cured and carved into bowls and spoons and cat’s claw acacia and Peruvian pepper tree were used for glue.

At Mission Santa Barbara, Tina Foss, Curator of the mission museum and Jerry Sortomme, Professor Emeritus of Santa Barbara City College have been actively restoring a huerta in the mission grounds. They have sourced several plants that can be traced to one or another of the early mission gardens. A cutting from a grape plant known to more than one hundred years old from Gypsy Canyon Winery was tested for DNA. The plant was shown through the tests to be the original ‘Mission Grape’ (known as the ‘Criolla Chica’ in Argentina,’ ‘Negra Corriente’ in Peru, and ‘Pais’ in Chile; Robinson, 1999). Another (untested) grape cutting was obtained from San Ignacio Mission in Baja California from a grape vine known to be more than 250 years old, thus dating from the time of the establishment of the missions. Ancient cuttings of pear trees from La Purisima Mission in Baja (circa 1800) and from Rio Hondo may prove be the original pear variety ‘Padre.’

Some varieties of vegetables originally grown at the missions in the late 1700s and early 1800s are still available in commerce, and some might be sourced from other historic collections. Most of the herbs are still available; several old varieties of beans, squash and maize are still to be found, as well as lettuces, gourds, melons and chili peppers. Very few peas, carrots, cabbage, cauliflower, onions, and tomatoes have survived; however, I have sourced at least one late eighteenth or early nineteenth century variety of each of these.

DRAWINGS OF CURRENT GARDEN AND A HISTORIC RECONSTRUCTED HUERTA

The drawings I have made show: first, the original layout of structures at the mission, taken from drawings made in a survey of the site in 1933. The second drawing shows the current, historically inaccurate East Garden with cement paths, grass and the fountain moved about 30 feet east of its original location. Third, my plan for the reconstructed huerta, showing overall design of paths and beds, with the fountain restored to its central location. My fourth drawing shows a detail of one of the beds with mixed vegetables, fruit, herbs and flowers, typical of the late eighteenth-early nineteenth century Spanish Colonial style. Existing large olive, palm and pine trees have been retained as part of the reconstructed design. The fifth illustration is a watercolor painting showing what the restored huerta would look like.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

AthanasiusSchafer.com. Mission San Fernando Rey de Espana.

Glybok, Shirley, 1972. The Art of the Spanish in the United States and Puerto Rico. NY: McMillan.

Brenzel, Katherine, Ed. 2001. Sunset Western Garden Book. Sunset Publishing, Menlo Park, CA.

Hayes, Virgina, Jan. 23, 2007. “A Huerta for Mission Santa Barbara” Santa Barbara Independent.

Padilla, Victoria, 1961. Southern California Gardens. Los Angeles: University of Caliifornia Press.

Los Angeles County Library.org. Mission San Fernando.

Rivera, Jose A and Thomas F. Glick, 2003. Local Control and Discretionary Authority: Protecting the Acequia Bordo. From a paper presented at the 51st Congreso Internacional de Americanistas, Santiago Chile, July 14-18, 2003.

Robinson, Jancis, Ed., 1999. The Oxford Companion to Wine. NY: Oxford University Press.

Streatfield, David C., 1994. California Gardens: Creativity and a New Eden. New York: Abbeville Press.